After having spent a month building experimental and DIY instruments with their mentor Yuri Landman, our July Mentees Obi Blanche & Brad Nathanson had a conversation about their work in progress during the residency – releasing as well their new tracks “Terraforming” and “Rake” that you can listen below!

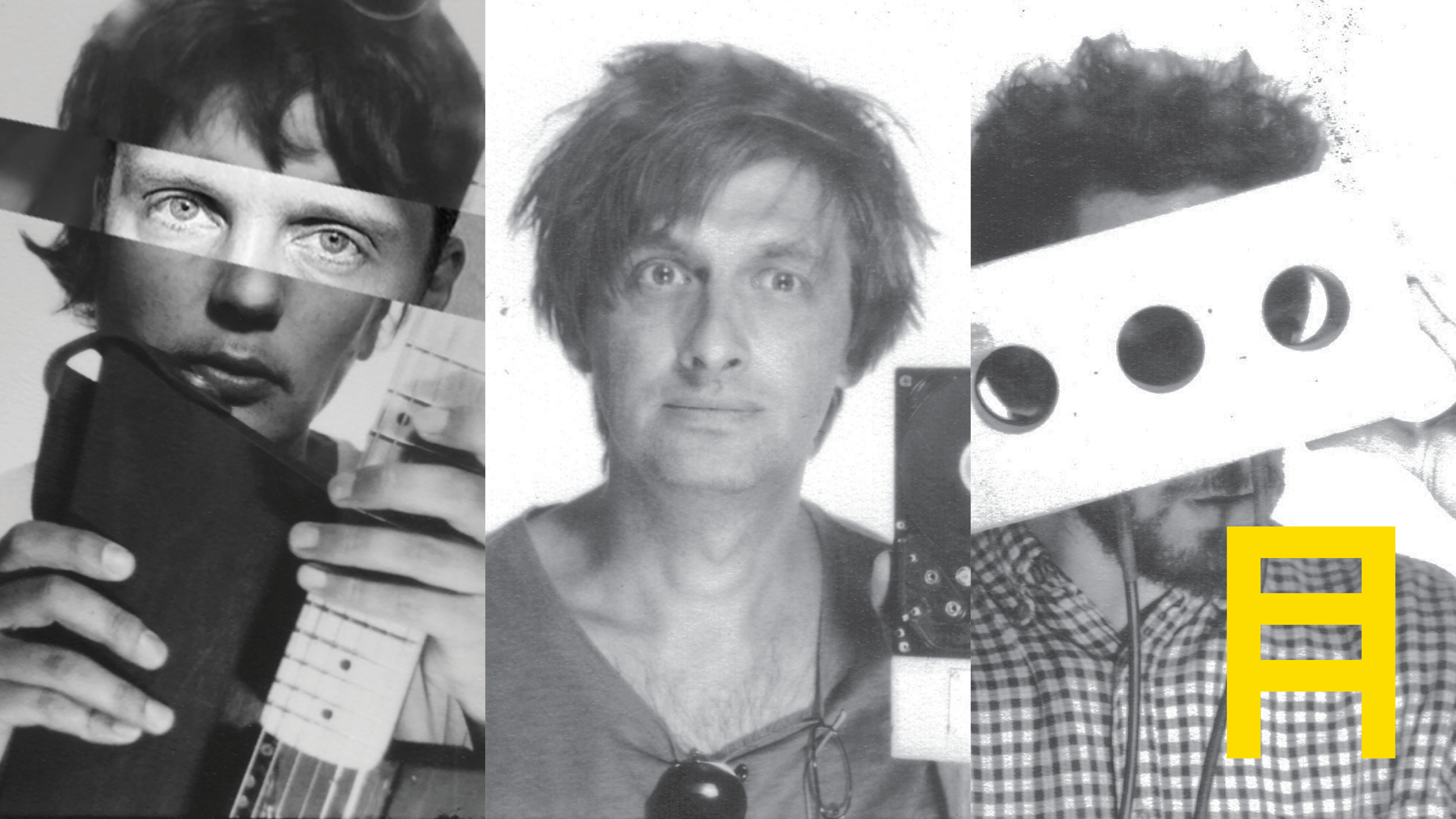

L to R: Obi Blanche, Yuri Landman, Brad Nathanson

Brad Nathanson: Walk me through the evolution of the rake throughout its lifetime. What inspired the design? And how was it for you to build the instrument with the same hands that you now play it with?

Obi Blanche: I’ve been collecting ideas and re-searching different possibilities to build an experimental guitar since I started playing as a child. I was always interested to get non guitar like sounds out of the guitar, first synth type of sounds and then finally back to the acoustics of the guitar and how to make the guitar sound interesting starting from the guitar itself. Yuri Landmanns book ‘Nice Noise’ is a great beginning to start modifying the guitar and some of these techniques I have used before finding the book, but there’s still plenty there I haven’t even tried. These days I don’t shine away how a guitar by itself can sound, I’m intrigued by the initial sound source. There’s a lot of ground to cover there. Last few years I’ve been following experimental builders all around the world. I’ve been lucky to get to know personally the artist Schneider TM and his signature guitar ‘Fireschneider’ build by Deimel, which blew me away by the many new interesting solutions that they implemented to the guitar. I got to test run ‘Fireschneider’ and Yuri’s design ‘ White Eagle’ in the studio and they both were hugely inspiring.

I have always loved the weird and quirky vintage designs from Russia and Italy, the big bodied guitars. I always knew that my first own designed guitar is going to be big, bigger than anything on the market. I wanted it to be light weight too, the lightest guitar I’ve ever had. I think it’s pretty much the same weight as my Jerry Jones short scale Long horn, it’s light.

Yuri’s philosophy to guitar building was to make all the cuts by hand and sweat and that enabled me to connect with the guitar already at the building point. Hand sawing, hand sand papering. It was limiting and freeing at the same time. It was comparable to Karate Kid sort of a moment where the Sensei tells him to paint the fence with a certain movement and the kid doesn’t get the connection first, but then at the last match against evil he’s swiping the hits and kicks like a real proletarian and comes off clean. Rake is the eccentric kid with big ears, who’s the most loved, and ends up in the roster of Midland agency.

BN: I’m curious about your relationship with the rake now that you have been playing it for a couple weeks. What does it introduce to your creative process and how does it differ from your other guitars?

OB: We fell in love pretty much at the shaping process. When I connected the neck to the body and held him in my arms for the first time I knew this is going to be special. What came to the setup of the guitar I had different steps, this current version shaped up week after week. I took him to the studio and recorded with Thomas Azier with Rake v1, got some ideas and went further. I had 7 strings, with 2 highs crossed as a percussive sitar sound, went back to 6. I wanted 4 separate outputs, one piezo, one bass string, one master and one behind the bridge and 2 kill-switches. The behind the bridge is special, it’s perfect octave harmonix from the open string. This is based on Yuri’s overtone theories and to his calculations and bridge positions and string lengths. Rake is most comfortable tuned to baritone tuning. I’m starting from A. That already influences the playing, everything influences the playing. I feel I’m tapping in to a complete new territory of guitar. I’m looking at it differently. Rake is not a jewel, Rake is a raw instrument that came to be through hard work and thus is priceless.

BN: While rehearsing for the live set you spent a lot of time improvising in the club with the rake. I sat in on a few of these sessions. Can you talk about what this experience of becoming acquainted with the instrument was like for you? What did you discover?

OB: Those sessions were a blessing, I discovered so much those days spent in the club. I had a stereo amp setup with EHX 2880 4-track looper and a Headrush Pedalboard that could loop too. I found out that to be dark and murky was quite easy, so after a couple of days I went out to the sun and realised that I don’t want to do this, I want to play yellow. I changed the tuning to open A major and got completely lost on the fret board. I needed to start from the scratch, I didn’t know what to play and how to play. I spent 2 days on the fret board, even tuned my parlor Höfner to be in an open tuning to be able to play before bed time. Finally I started to see the patterns of the a – e – a – e – a – c# tuning and got more comfortable with the idea of improvising for half an hour. Meanwhile raking the club floors with Rake I discovered many different sounds that inspired me. One of these is a way of playing with a bow I call ‘snoring man’, self explanatory sound. Yuri told me it’s a technic invented by Hans Reichel and sound created by the Daxophone, but he never heard it been made with the guitar before. These new techniques going to be heard on a new Thomas Azier record and on a theme song for Rake called Rake.

OB: Why bricks?

BN: Why not?

In a city like Berlin they are everywhere and nowhere at the same time. We live our lives within bricks, yet we pay no attention to them. What might we be missing?

My interest in bricks began during my time in architecture school. I wanted to cast a speaker inside of concrete and listen to the sound of the inside. At first, the brick had nothing to do with it though—I built a simple formwork, suspended the speaker, and poured the concrete to fill the void. It wasn’t until after that I began to understand this object as a brick. The fact that the natural form and scale of my first test created a kind of brick is partly the reason why I am so interested in them. There is some certainty to the brick.

Many people tell me that the brick is “dumb”. I wouldn’t use that word…I think what they mean is that it is foundational. It was and sometimes still is the literal building block for agrarian civilizations throughout the planet. I’m not sure yet, but maybe the brick is even the fundamental module of the Anthropocene…

I often wonder whether people think that my work is a celebration of the brick. I don’t think of what I do in this way. Rather, I understand what I do with bricks as a way to reflect on the object’s capacities, politics, and potentials. Maybe by providing sonic agency to the brick there are things to hear about the world we have built for ourselves.

OB: Why sound?

After hearing many times that “architecture is frozen music”, I stopped believing it. The idea that the built environment can be frozen in any way, to me, stems from a false nature–culture divide. I realized that architecture, like any environment, is constantly vibrating. I wanted to listen to its sonic vocabulary.

We spend our lives within concrete but have no idea what it sounds like…we tend to think of it as extremely dense, but after listening to microphones embedded inside it actually sounds very fragile, almost glass-like.

In “Terraforming”, the track that I made this month, I recorded all of the samples from within concrete, silicone, and plaster bricks that I built. Each brick has two microphones inside and outputs a stereo signal that varies depending on which surface is touched. Because the materials themselves are already artificially processed, I left the samples mostly unprocessed except for, on some occasions, reverb.

Sound is an incredible form of communication between disparate bodies. It brings them together…I felt that there could be much to be gained by placing microphones beyond the surface of the surfaces that enclose my daily life, where my body could not go. I still wonder what we can gain from experiencing reality from the perspective of these materials.

OB: Why juxtapose that with the human body?

BN: I think the desire to include the human body in my architectural research was there from the first performance four years ago. For a while I felt that rather strangely, architects didn’t design buildings for the human bodies that would inhabit them. I wanted to find a way of doing architecture that dealt directly with bodies. While I use amplified bricks for material research, sound installation, and recorded music, I have by far used them the most in live performances.

The performance that you saw was the result of four years of a slow but natural development. In my early performances I worked to deemphasize my body, in an effort to bring attention to the bricks. Now I understand that the bricks and I are equal actors, and that the live set is about demonstrating this relationship.

I am not interested in the built environment in isolation. Rather, I am curious about the ways that architecture imposes itself on its inhabitants. I want to reveal the built environment’s formalized motives by amplifying them. Perhaps then we can understand how an environment’s sonic agency is structuring our bodies, even when it is turned off.